Iron ore is regularly transported by train from Sweden to the Norwegian coast, one example of the growing number of infrastructure projects connecting the Arctic to the rest of the world. (Image Source: © Own work: http://www.bahnbilder.ch/picture/3324)

Development, economic activity and investment within the Arctic region is intensifying. As the sea ice in the Arctic Ocean retreats, federal governments and the private sector are increasingly focusing their engagement and finance on infrastructure in the region. New ports and harbours, mines, gas and oil pipelines, roads, railways, coastguard facilities and airports to serve the Arctic are materialising at accelerating speed. Much of this development is taking place organically or incrementally, but as this proceeds consideration needs to be given to the physical, environmental and societal impacts of these changes, how they can and should be managed and optimised for the benefit of local and indigenous communities, the Arctic environment and wider regional economy. The recent growth in infrastructure is no small or minor trend, with $300 billion in projects either completed, in motion or proposed in Russia alone.[1] It is also here that the Russian Federation emerges as the clear leader in Arctic infrastructure, followed closely by Finland, Norway, Canada and the United States that have each proposed significant infrastructure investment within their own respective Arctic areas.[2] It is the entrance of China though, with its Polar Silk Road Initiative, comprehensive Arctic Strategy and underwriting of development in the region despite having no territorial claim there, that has been the real game changer, serving to clearly demonstrate the region’s growing global importance.[3]

An inventory of planned, in-progress, completed and cancelled Arctic infrastructure projects compiled in 2016 by global financial firm Guggenheim tallies 900 projects, amounting to an estimated one trillion dollars of infrastructure investment over the next 15 years.[4][5] This is no small or localised economic trend. This ‘opening of the Arctic’ presents both a challenge and an opportunity for a new chapter in development, politics, economics and human affairs. While there are many risks and sensitivities involved, this new chapter is also a powerful one. A chapter in which all Arctic nations and partners could come together to champion the best in sustainable and inclusive design, in order to avoid the mistakes of the past, ensure the best results, and pursue a holistic approach to infrastructure development. As a key feature of this there exists a strong case for articulating a new Arctic Accreditation Scheme for the built environment – a framework and gold standard for the critical mass of infrastructure and development proposed. In turn this also represents an opportunity for the Arctic region too; a sparsely populated part of the world, but a geopolitically powerful one, on the ascendance and capable of demonstrating to the world how it is uniquely placed to be a global leader in robust and sustainable development.

Through the expansion in shipping via new Arctic sea routes, increasingly accessible coastlines and the opening up of new opportunities for resource extraction in the Arctic, the need for a robust, yet flexible, approach to infrastructure development has never been more pertinent than today. By way of an example, cargo transit along the Northern Sea Route reached a volume of seven million tons in 2016, rising to 17 million in 2018 and is assessed to reach 75 million tons per year by 2025.[6][7] With these figures in mind, Russia has been proceeding apace with the construction and development of dedicated deep-water Northern ports and associated infrastructure along its Northern and Eastern coastlines, with $300 billion already invested,[8] and another $82 billion declared in investments over the next five years.[9]

All too often though while billions of dollars of infrastructure is being built, this is typically in response to short-to-medium term and isolated needs, usually to exploit local resources with limited regard for any associated negative impacts for the environment and local population. One such example of this is the intensive expansion of JSC’s Vostochny (Nadkhodka) Port in the Russian Far East, principally for the purpose of significantly increasing coal loading and export, mainly to East Asia and Europe, but which locals and environmental groups complain has been built and is being operated without any adequate protections for the health of the town’s inhabitants or the natural environment.[10] Although Russia has invested in opening a 9,100km dedicated Moscow-to-Vostochny rail service, transporting cargo and container services to and from the port, which operates weekly. [11]

Figure 1: Identified Arctic Development Sites Along With Shipping Routes (Source: WWF,[12] Graphic: © Ketill Berger, filmform.no – Source: © Guggenheim Partners, Natural Earth)

This picture is not a uniform one though either. While Russia is actively investing billions in building new maritime facilities as well as supporting infrastructure, the existing infrastructure in other Arctic states is being developed in an uneven manner, with areas even falling into disrepair and disuse. Arguably, Canada’s Arctic infrastructure is one such example, as it is not being developed in a truly holistic and joined-up fashion. While federal dollars are being spent on infrastructure connecting the interior with coastal Arctic port communities, no investment has been made in those port facilities. Indeed, the recent struggle to maintain and then the subsequent closure of the Port of Churchill in 2016, Canada and North America’s only deepwater port capable of handling Arctic shipping with access via rail to most of North America, exposes the challenges that Canada has had with investment in Arctic infrastructure.[13]

Admittedly, the Canadian government has been investing in Arctic infrastructure, with projects such as with the $300million (CAD) year-round highway connecting Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk, providing the first ‘all-weather road to Canada’s Arctic Coast’. Locals and government officials alike are anticipating a deepwater port in Tuktoyaktuk to follow, so much so that the road even earned the moniker ‘the world’s longest boat launch’.[14] However, the ability of this road to actually service a port was never fully considered, nor factored into the design process and the road’s weight restrictions, raising many questions about its fitness for purpose. While early indicators do support the case that the road development may bring social and economic benefits to remote communities, as can be evidenced by increased access to healthcare, education and tourism, the road’s utility as infrastructure to service an Arctic port is severely limited.[15][16]

Figure 2: The Tuktoyaktuk to Inuvik All Season Road. (Source: BBC, [16] Graphic: © Mike MacEacheran)

With a historic affiliation to oil from operations in Beaufort Sea, as well as use for coal, timber and grain exports, Tuktoyaktuk has been well placed for many decades, equipped with an existing, albeit small, port facility at which vessels traversing the North West Passage now call.[17] Tuktoyaktuk already has a relatively deepwater port, but suffers from a shallow approach channel, a high degree of in-fill silting and its existing underdeveloped infrastructure, which limit the size of vessels that can berth.[18] Given the lack of any other appropriate or deepwater ports along the entire northern Canadian coastline, Tuktoyaktuk is strategically-positioned as a key location for Arctic shipping, as well as for the implementation of safety preparedness across the Arctic Ocean. There is a case here for the upgrade to an active deepwater port. However, weight restrictions and other design flaws in Tuktoyaktuk’s recently completed highway, combined with on-going road closures, have already severely limited its potential. Arguably, the design and construction of this road did not consider the full scope of its use for the wider region and its economic activities, which raises questions about its strategic value as an investment and whether it represents a missed opportunity. This example in turn posits an important question; could a more holistic framework and agreed set of standards for Arctic infrastructure help prevent such oversights in the future and ensure better value for money?

Standing at the vanguard of what is estimated to become extensive development across the Polar Regions, with a moment to consider the next wave of construction, it can be argued that there currently exists a unique opportunity to take a more enlightened and strategic approach to Arctic development. This is an opportunity to learn from both the mistakes and successes of the Arctic’s past, as well as through the appreciation of the many and varying development attitudes around the globe, and to approach new Arctic development in a new and much more holistic way than before. Recent years have shown that polar construction projects have become more attuned to their environment and context, with some smaller-scale holistic thinking on stakeholder engagement, as well as project management and construction, often driven by the remoteness, inaccessibility and local community needs of the High North. This represents an excellent starting point for how to ensure projects are appropriate to their context and tailored to their needs.

Current environmental changes such as retreating multiyear sea ice and thawing permafrost are not only opening up the Arctic Ocean and landscapes to commercial activities, but are also exposing coastlines to increased erosion and subsequently affecting coastal communities, causing existing infrastructure to collapse and impacting food and water resources upon which local communities depend.

Consideration of the existing approach to built infrastructure, coupled with the increased exposure of the Arctic regions and developing environmental factors, suggests a larger scale holistic approach to infrastructure projects across the High North is required. Through this, sufficient clout will be held to be able to champion sustainable development too. A wider holistic approach may encompass water, waste and energy production, reduction and re-use, energy-positive construction as well as multi-purpose, flexible, resilient and adaptable infrastructure. Development within the Arctic could not only exhibit first-rate engineering and construction standards, but could also be used to bring benefits to society as well. This is especially true if economic investments are directed to target sustainable construction in line with the World Economic Forum’s Arctic Investment Protocol, first launched in 2016, which set out a path towards the more inclusive, transparent, accountable and sustainable development of the Arctic for all inhabitants.[19] The protocol was a world first, and it articulated six key principles for Arctic investment:

1. Build resilient societies through economic development;

2. Respect and include local communities and indigenous peoples;

3. Pursue measures to protect the environment of the Arctic;

4. Practice responsible and transparent business methods;

5. Consult and integrate science and traditional ecological knowledge;

6. Strengthen pan-Arctic collaboration and sharing of best practices.

Given the level of support that the WEF’s Arctic Investment Protocol (AIP) succeeded in securing, with the backing of 22 senior executives from multinational corporations such as Pt Capital, Barclays and China’s COSCO Shipping Corporation, as well as an official endorsement from Guggenheim Partners,[20] any Arctic-wide Sustainable Development framework for the built environment, infrastructure and construction standards should look to build upon this model as a foundation for articulating its own requirements. “To adapt and thrive”, Guggenheim noted in its official endorsement of the protocol, “Arctic communities need critical and careful investment today, paired with a strong commitment to protect and preserve the environment for future generations. Sustainable development therefore is a generational imperative”.[21] The AIP represents a solid foundation on which to establish and build an Arctic-wide framework for development; compelling companies and organisations, engineers and designers to measure their work to a higher standard.

Being at the vanguard of major development within the High North also allows for the implementation of low impact subsistence technologies, such as solar, wind, geothermal, permafrost methane capture and ocean energy capture that will promote and encourage greater dependence on community-led infrastructure. In extension to local considerations, any wider holistic approach ought to bear in mind the need to encompass both existing infrastructure and communities, as well as new developments. An example of this would be the development and adaptation of existing coastal settlements and major infrastructure to serve Arctic-wide needs, such as developing resilience against accelerating rates of coastal erosion and flood resilience as well as increased shipping needs, not seeing them as two separate challenges.

Considering that Arctic coastline erosion is now being seen at a rate of tens of metres per year and that the rate of sea level rise is also accelerating,[22] the current code-based allowances for sea level rise used in the design of coastal infrastructure around the world are no longer applicable. In some instances, the estimate of sea level rise has doubled over the course of four years for select emissions scenarios.[23] The need for truly flexible, resilient and adaptable port and coastal construction is therefore pressing and one that could even support the premise for more radical style of floating infrastructure.

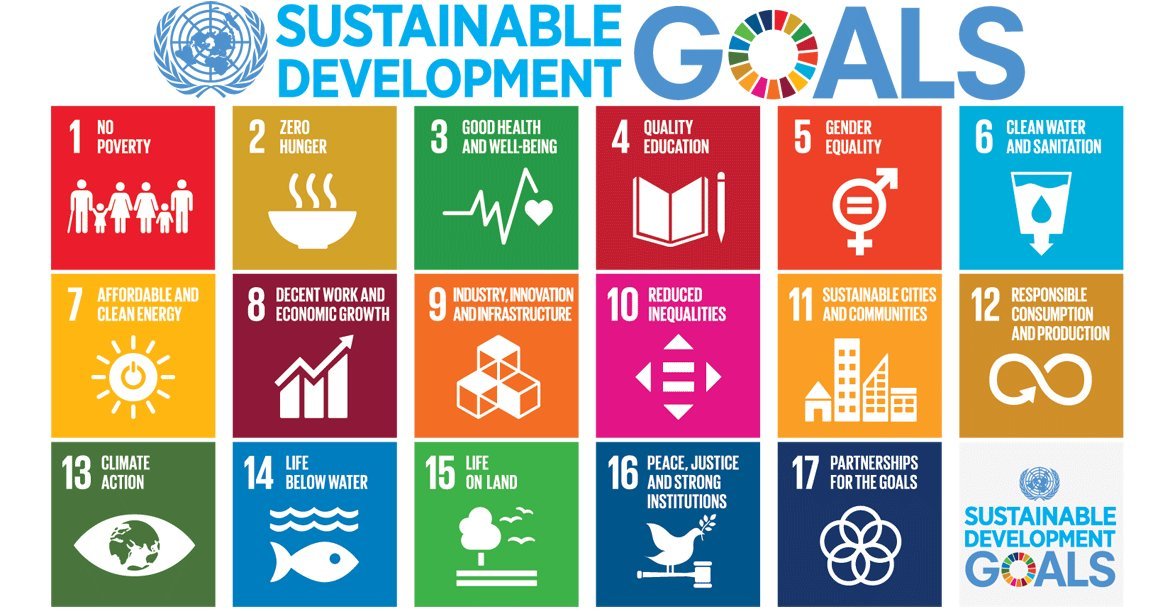

An example of a holistic sustainable programme of development may best be visualised through the 17 Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs,[24] originally proposed by the United Nations in 2015 and subsequently adopted by the Arctic Economic Council and the Arctic Council. The goals most targeted to the built environment and its governing legislation include: Affordable and Clean Energy (Goal 7); Decent work and Economic Growth (Goal 8); Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure (Goal 9); Sustainable Cities and Communities (Goal 11); Responsible Consumption and Production (Goal 12); Climate Action (Goal 13); Life Below Water (Goal 14); Life on Land (Goal 15) and Partnerships for the Goals (Goal 17). Through targeting development in the High North around these goals, the built environment will go a long way to enable a suitable platform for the achievement of the rest.

Figure 3: The United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (Source: © United Nations )

An example of the successful implementation of the above SDGs is the Svart Hotel in northern Norway, located at the base of the Svartisen glacier, near Bodø.[25][26] The hotel will be the world’s first energy-positive hotel, an accolade achieved by the harvesting of its own energy. Aside from this, the hotel will also reduce its energy consumption by an impressive 85 percent compared to other modern hotels, implementing numerous energy-positive initiatives that have already set a new standard in sustainable tourism.[27]

Within the Arctic regions, existing remote communities survive without much of the infrastructure that urban populations take for granted. A recent review by the Arctic Council of water and sanitation services in the Arctic reveals that small rural communities have little or no access to improved water and sanitation and conjunctly have no connection to wider infrastructure such as roads or distributed power.[28] Where the issues surrounding water and sanitation should undoubtedly be addressed, the latter is a prime example of where a balanced, holistic and sympathetic approach to development should be applied. When considering an infrastructure model ‘fit for urban areas’, the cost of providing matching infrastructure provision for isolated rural communities is seen as prohibitive. It is exactly these communities, however, that any future development still needs to support. These situations provide excellent scope for the implementation of sustainable, community-owned infrastructure, and it is the experience of these communities that will help shape future Arctic development.

Development for the sake of development, however, must be avoided. Prioritising self-sufficiency over any reliance on global supply chains should be promoted, and sustainable development should be directed to maximise human, social, economic, legacy and environmental benefits, as per the 17 SDGs and the Arctic Investment Protocol. In addition to providing for material needs, development can then instead be used as a very powerful tool to elevate communities and to expand people’s horizons.

Figure 4: An Architect’s impression of the proposed Svart Hotel, the world’s first energy positive sustainable hotel.

(Graphic: © Snøhetta/Plompmozes)

The expansion of people’s horizons through infrastructure can include the development of education, trade, amenity provision and entertainment, and can be used to up-skill the population and provide new purposes for communities that have lost their old sources of sustenance/income. A prime example is the training of local people in the skills required to develop their local area as they themselves require and demand. Infrastructure development in turn tackles the remaining SDGs, providing opportunities for long-term improvements in prosperity and health (Goal 3), reductions in poverty and inequality (Goals 1, 10), tackling issues of hunger (Goal 2), quality education (Goal 4), gender equality (Goal 5), and provision of clean water and sanitation (Goal 6).

The environmental benefits of sustainable development include effective reuse and longevity of materials and the built infrastructure, as well as a reduced carbon footprint. This provides long-term economic and social gains such as good environmental stewardship. Additionally, the built environment, through proper planning, can benefit the interaction between humans and the natural environment. It is these two points that support Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions (Goal 16).

Starting afresh, we have an opportunity to build minimally, robustly and appropriately. Only as required, and to avoid consumer-driven mind-sets. Around the globe, development has typically gone hand-in-hand with material prosperity and access to a global supply chain, reinforcing the perception that international products are normal and acceptable by masking their true environmental costs.

In this global supply chain, over 90% of the world’s traded goods are transported by sea,[29] which also carries significant negative environmental impacts. Global shipping is responsible for 3.1% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, 13% of global sulphur oxide (SOx) emissions and 15% of nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions per year.[30] Within this, Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO), currently used by some Arctic-going vessels, is recognised as the worst offending form of pollution.[31] Additionally, the consequences of an HFO spill are particularly hazardous given the relative ineffectiveness of oil dispersants, and a dramatically reduced ability to enact clean-up operations once oil dispersion underneath sea ice has occurred.[32] Current tougher energy efficiency standards will help curb pollutants in the future, but unfortunately these do not apply to current vessels. There is, however, rising political, economic and market pressure to phase out HFO usage through The Arctic Commitment; an international campaign to ban HFO powered vessels from the Arctic and to move the shipping industry onto less carbon-intensive forms of fuel.[33] The Arctic Commitment is also notable as a campaign of which Polar Research and Policy Initiative is a proud signatory. This example also highlights how further work needs to be done in the design of infrastructure, as well as any associated accreditation schemes, to support and encourage more sustainable, carbon-neutral forms of goods transportation and related facilities, now and in the future.

In addition to environmental considerations, the global supply chain, specifically shipping in the Arctic, is also vulnerable both to physical and political constraint. This may include extreme weather conditions, rapidly changing product demand, control of shipping routes, and lack of safety and response services. This is another area in need of more holistic consideration.

To realise minimal, robust and appropriate sustainable development, equally rigorous guidance and control must be established through strong institutions and is likely to include:

The question remains, however: how do we achieve a holistic approach to High North infrastructure projects? Principally one that best champions sustainable development and optimises the collective lessons learnt from infrastructure around the world. The answer is to be found in the below five areas;

The issue at hand here is that there is no existing, overarching Arctic-wide sustainable accreditation scheme available. Policies and guidelines are limited to national country-specific regulations, aside from the recommendations laid out by the European Union and the Arctic Council’s Sustainable Development Working Group. Therefore, there exists a strong case for the development of a new, truly holistic Arctic-wide sustainable development accreditation scheme. A framework and gold standard for both Arctic infrastructure and its built environment. This scheme would ideally build upon the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, draw on best practice and eventually become mandatory for all development within the High North. Given the nature and challenges of the Arctic environment though, this scheme would obviously necessitate some flexibility and should be formulated conjointly with the very latest technical standards and rigorous planning policy. Within the Arctic, projects exhibiting low standards and reckless construction should be treated with a zero tolerance approach, and thus any Arctic-wide scheme should be enforceable, with incentives for compliance and penalties for circumvention.

Figure 5: Iqaluit Airport in Nunavut, Canada. A positive example of public-private partnership incorporating sustainable

accreditation and stakeholder engagement to achieve a successful outcome. (Image: © Bouygues Construction, 2017)

Holistic, sustainable development within remote or hostile High North environments also comes with a number of specific challenges, as outlined below;

Figure 6: An architect’s impression of the Port of Longyearbyen’s Floating Terminal in Spitsbergen, Norway.

(Graphic: © Snøhetta Architects)

If the aforementioned challenges can be successfully overcome, then there are significant benefits that can be conferred through good design principles and schemes such as Whole Life Costing (WLC). Robust and well-considered design has been proven to save money, lower operational and maintenance costs, reduce environmental impact, improve building and infrastructure performance, extend a project’s lifespan and boost productivity.[37] It is a key measure in the built environment of improving a built asset’s long-term value for money. WLC works best when input takes place right from the start of a project and proceeds through all the stages of design, construction, use and decommissioning, with constant evaluation, feedback and optimisation.[38]

Linked with a sustainable accreditation scheme and rigorous design standards, therefore, WLC would be an effective way to determine the viability of a project and is an appropriate vehicle to drive for efficiency and value. Proof of ‘cradle to grave sustainability’ within a needs-based infrastructure is an approach that would have ample applicability within the Arctic, preventing the oversights that took place at Tuktoyaktuk, among other projects.

Environmental change across the Arctic is opening up the High North to development. With one trillion dollars of infrastructure investment anticipated across the Arctic in the next 15 years, society is in a unique position to champion the very best in sustainable and inclusive design. Drawing on the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, the High North can promote the very best development as required and driven by local communities, means-tested against rigorous strategic objectives. Given a largely remote and challenging environment, the High North provides a perfect platform for the implementation of locally-driven infrastructure and cutting-edge technology.

However, given that we are now on the cusp of widespread Arctic development, in order to avoid a rat race and degradation of the High North environment, an Arctic-wide Development Framework or accreditation scheme should be implemented to critically assess infrastructure needs and to drive the very highest standards. An Arctic-wide framework for development would help ensure that stringent yet flexible planning processes were implemented, as well as pan-Arctic cooperation and adherence to internationally-recognised technical standards for construction and operations. This could take the form of an Arctic framework or accreditation scheme, drawing on the UN’s 17 SDGs and the Arctic Investment Protocol, whilst incorporating the lessons from Whole Life Costing and other international sustainability standards, by recognising the long-term benefits that they confer upon users, assets and the environment. If there was also the will and determination among all eight Nations of the Arctic Council to sign up to such a framework, then the Arctic would have a powerful standard against which all developments, contractors and companies could be held.

It is the views of the authors that humanity should always endeavour to showcase the manifold benefits of what human ingenuity and sustainable design can achieve, for the mutual betterment of all peoples and societies. It is here, on that principle, that the Arctic has the real and tangible potential to demonstrate exactly this. Standing on the cusp of a new chapter in development; the ‘opening of the Arctic’, but with the time to pause, to consider implications and the manner in which we carry out that development in such a sensitive and important part of the world, that we can act to push the boundaries of human ingenuity, compassion and the integration of technologies. With determination and foresight, we could ensure minimal pollution and environmental damage by demanding a higher standard in both energy use and mitigation measures. We could demand better value for money from our infrastructure and fitness for purpose, as well as enhanced and empowered indigenous engagement and quality of life, as well as crucially, more robust design and sustainability standards. In short, we can and should demand a better standard for the Arctic. Then, in turn, it will be the Arctic’s moment to lead, and to demonstrate to the world a new gold standard for how all infrastructure development should be planned, designed, built and operated. Something we could all benefit from.

[1] CNBC, “Russia and China vie to beat the US in the trillion-dollar race to control the Arctic” 06 02 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.cnbc.com/2018/02/06/russia-and-china-battle-us-in-race-to-control-arctic.html. [Accessed 29 12 2018].

[2] CNBC. (Ibid).

[3] European Parliament, “China’s Arctic Policy” 05 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/620231/EPRS_BRI(2018)620231_EN.pdf/. [Accessed 29 12 2018].

[4] Guggenheim Partners, “Guggenheim Partners Endorses World Economic Forum’s Arctic Investment Protocol,” Guggenheim Partners, 21 01 2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.guggenheimpartners.com/firm/news/guggenheim-partners-endorses-world-economic-forums. [Accessed 3 11 2018].

[5] CNBC. (Ibid).

[6] Arctic Today, “Traffic on Northern Sea Route doubles as Russia aims to reduce ice-class requirements,” Arctic Today, 26 11 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.arctictoday.com/traffic-northern-sea-route-doubles-russia-aims-reduce-ice-class-requirements/[Accessed 20 12 2018].

[7] J. Louppova, “Russian port capacity grows with new projects”. Port Today, 23 02 2017. [Online]. Available: https://port.today/russian-port-capacity-grows-with-new-projects/. [Accessed 28 10 2018].

[8] CNBC. (Ibid).

[9] ARCTIC TODAY, “Russia presents an ambitious 5 year plan for Arctic Investment,” Arctic Today, 14 12 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.arctictoday.com/russia-presents-ambitious-5-year-plan-arctic-investment/ [Accessed 20 12 2018].

[10] K. Golubkova and O. Kobzeva, “Eastern Russian port of Nakhodka chokes on coal,” REUTERS, 21 12 2017. [Online]. Available: https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-russia-coal/eastern-russian-port-of-nakhodka-chokes-on-coal-idUKKBN1EF1HG. [Accessed 4 11 2018].

[11] Port News, “VSC terminal launches train services to Ramenskoye Station,” PORTNEWS, 19 03 2018 .[Online]. Available: {/. [Accessed 01 10 2018].

[12] WWF ARCTIC PROGRAMME, “The Circle,” 03 2018. [Online]. Available: https://arcticwwf.org/site/assets/files/1269/thecircle0118_web.pdf. [Accessed 08 11 2018].

[13] M. Bennett, “What does the sudden closure of Canada’s only Arctic deepwater port mean for Arctic shipping?,” CRYOPOLITICS, 02 08 2016. [Online]. Available: http://www.cryopolitics.com/2016/08/02/what-does-the-sudden-closure-of-canadas-only-arctic-deepwater-port-mean-for-arctic-shipping/. [Accessed 23 09 2018].

[14] M. Bennett. (Ibid).

[15] M. MacEacheran, “Tuktoyaktuk: Canada’s last Arctic village?,” BBC, 19 04 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20180418-tuktoyaktuk-canadas-last-arctic-village. [Accessed 24 09 2018].

[16] M. Bennett. (Ibid).

[17] M. Bennett. (Ibid).

[18] ARCTIS, “Arctic Ports”. [Online]. Available: http://www.arctis-search.com/Arctic+Ports/. [Accessed 08 11 2018].

[19] World Economic Forum, “Arctic Investment Protocol: Guidelines for Responsible Investment in the Arctic”, WEF, 2016 [Online]. Available: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Arctic_Investment_Protocol.pdf [Accessed 30 10 2018].

[20] Guggenheim Partners, “Guggenheim Partners Endorses World Economic Forum’s Arctic Investment Protocol”, 21 01 16. [Online]. Available: https://www.guggenheimpartners.com/firm/news/guggenheim-partners-endorses-world-economic-forums/. [Accessed 01 02 2019]

[22] K. Weeman and P. Lynch, “New study finds sea level rise accelerating,” NASA, 13 02 2018. [Online]. Available: https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2680/new-study-finds-sea-level-rise-accelerating/. [Accessed 24 9 2018].

[23] J. Tollefson, “Huge Arctic report ups estimates of sea-level rise,” Nature, 28 04 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.nature.com/news/huge-arctic-report-ups-estimates-of-sea-level-rise-1.21911. [Accessed 24 09 2018].

[24] United Nations Development Programme, “Sustainable Development Goals,” 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html. [Accessed 4 9 2018].

[25] Snøhetta, “Svart,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://snohetta.com/projects/366-svart. [Accessed 22 09 2018].

[26] N. Myall, “Snøhetta designs “Svart” – The world’s first energy positive hotel,” WORLDARCHITECTURENEWS.COM, 12 02 2018. [Online]. Available: http://www.worldarchitecturenews.com/project/2018/28463/sn-hetta/svart-in-svartisen.html. [Accessed 10 11 2018].

[27]N, Myall. (Ibid).

[28] Arctic Council Sustainable Development Working Group, “Results of an Arctic Council Survey on Water and Sanitation Services in the Arctic,” Arctic Council, 2011.

[28] Business.un.org, “International Maritime Organization,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://business.un.org/en/entities/13/. [Accessed 4 9 18].

[29] International Maritime Organization, “REDUCTION OF GHG EMISSIONS FROM SHIPS Third IMO GHG Study 2014 – Final Report,” International Maritime Organization, 2014.

[30] HFO-FREE ARCTIC, “What are the Risks of Using Heavy Oil in the Arctic?,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.hfofreearctic.org/hrf_faq/risks-using-heavy-fuel-oil-arctic/. [Accessed 06 11 2018].

[31] HFO-FREE ARCTIC. (Ibid).

[32] HFO-FREE ARCTIC. (Ibid).

[33] HFO-FREE ARCTIC. (Ibid).

[34] The Government of Nunavut, “Iqaluit International Airport Project,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://gov.nu.ca/edt/documents/iqaluit-international-airport-project. [Accessed 10 09 2018].

[35] International Permafrost Association, “What is permafrost?,” 2015. [Online]. Available: https://ipa.arcticportal.org/publications/occasional-publications/what-is-permafrost. [Accessed 10 9 2018].

[36] H. K. Røsvik, “Rigger for mye mer trafikk,” Svalbardposten.no, 25 01 2018. [Online]. Available: http://portlongyear.no/rigger-mye-mer-trafikk/. [Accessed 23 09 2018].

[37] BRE Group, “Whole life costing and performance (WLC)”, BREgroup.com, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://bregroup.com/services/advisory/design/whole-life-costing/. [Accessed 30 10 2018].

[38] BRE Group. (Ibid).