The escalating trade war between China and the US may force Alaskan seafood into a difficult position, threatening livelihoods today and into the future. While there remain many unknowns, now that 25% Chinese tariffs have come into reality on 6 July, both countries are assessing the potential costs of building tariff walls between their growing fisheries trade and investment ties. A significant amount of Alaska’s exports to China are processed and re-exported to other countries. Strategic exemptions in the tariff to accommodate the re-export trade will soften the blow for both China and Alaska, and there is now an understanding that seafood for re-processing will be exempt from the tariff hikes. High value products like king crab, destined for luxury markets in China, may be hit more severely.

China has levied the tariffs on a wide variety of seafood products – 181 different HTS (Harmonized Tariff Schedule) codes, including pink and sockeye salmon, crabs, and groundfish. Though an official English language list remains hard to come by at this time, the Chinese list can be found here, with the relevant HTS codes. The list includes most seafood, with some exceptions such as items that are preserved (e.g. salted, smoked, brined) and processed fish fillets. The Chinese have given no particular explanation for the choices of items affected, and the US tariffs set to be imposed on China do not include seafood. But a likely possibility is that it will be relatively easy to meet Chinese seafood demand through substitute sources and species, since the markets are so globalized.

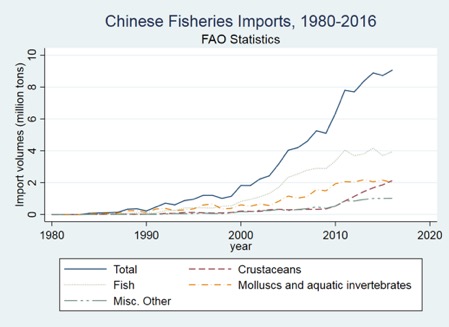

Adding to the potential relative impact, China had, just at the end of May, announced widespread tariff reductions starting 1 July for seafood products from countries with Most Favored Nation (MFN) status under the World Trade Organization (WTO). Now, other countries’ fisheries, competing with Alaskan products, may see a doubly positive boost at Alaskan fisheries’ expense. The Chinese seafood market is not one to be cut out of – the country is evolving from a fishing export nation to a fishing import/export nation, with growing wealth and cheaper, faster transport costs, meaning that Chinese demand for seafood imports has been growing. The graph below shows FAO data on the volume of Chinese seafood imports since 1980, in total and broken down in broad subgroups.

While all markets are growing, the rate of growth for crustaceans has particularly advanced. Annual average growth for Chinese imports of crustaceans from 1990 to 2016 was 14.7%, while from 2000 to 2016 it was even more rapid, at 16.7%. Overall annual average growth of all species imports from 1990 to 2016 was 12.3%, while from 2000 to 2016 it was 10.8%. Alaskan exports to China have particularly increased since 2011, so that China is currently Alaska’s biggest trading partner in value and volume.

Supply chains for seafood also stand to be disrupted. Recent Chinese investments by seafood giants like the vertically integrated industry leader Trident, as well as major e-commerce platforms, including business-to-consumer giant tmall.com, have intertwined Chinese and Alaskan fisheries so that raising costs for one can be expected to raise costs for both. As seen with the exemptions for re-processing, the Chinese do not seem interested in high self-inflicted damages, which should help mitigate problems for Alaska.

Working against Alaska, however, is the ease with which China might substitute Alaskan seafood products from other sources, including Russia, Canada and Chile. Estimated demand elasticities are high for luxury seafood like red king crab, meaning there is considerable substitution away from the species if price rises. The importance of this will depend on how long the tariff war continues. If successful new supply chains are built up from other countries, it will become more difficult for Alaska to work its products back into trade pathways. Furthermore, in the longer term, if China retreats from global imports due to tariff wars, and expands its investments in increased aquaculture, with which it has a long history of success, Chinese resilience to tariffs will grow as they reduce their dependence on imports of any sort.

Although the tariffs are not a complete surprise based on current US/China relations, it has put Alaska in a difficult position. In late-May of 2018, Alaska and China coordinated a series of meetings, networking opportunities and events in order to stimulate increased trade cooperation between Alaska and China. Although no large business deals were agreed upon during the meeting, it did open up the possibility for increased trade in seafood, natural resources, and new opportunities in tourism. These new seafood tariffs put a strain on the otherwise growing and beneficial relationship between the two entities.

The Alaska Seafood Industry was discussed on the third day of the official trade mission as a special breakout session. According to the Anchorage Economic Development Corporation readout of the meetings, there was a meet and greet event that targeted Chinese seafood buyers. During this event, the Alaska delegation discussed ways in which it could help expand demand for Alaskan seafood in China. Based on the AEDC information, the meeting was successful, and the Alaskan delegates speculated that there should be a boost in demand for Alaskan seafood, both fresh and frozen in the coming years. Chinese industry specialists identify Alaskan seafood products as a premium that is hard to match elsewhere in the world.

Based on the May 2018 trade mission and new tariffs, it is still unclear what the true impact on Alaska’s seafood industry will be. There is political will on behalf of the state of Alaska to continue and expand trade of seafood and other commodities with China. But without the US and China addressing the tariffs quickly, there could be a devastating impact on Alaska’s seafood exports.

Addendum: On July 10, the US published a new list of products that will face additional 10% tariffs to begin in September. As currently described, this will include re-imports of Alaskan seafood processed in China worth up to one billion USD.