Examining the history of UK’s Halley Station reveals much about advances in engineering and architecture. To look back at the various incarnations of Halley is to trace the evolution of the Antarctic station from functional shelter to architectural showpiece.

At first glance, Britain’s Halley VI Antarctic station looks more like an illustration from a sci-fi novel than an Antarctic research station. Eight pods, joined end on end, rear up against the vast expanse of the Brunt Ice Shelf staining it blue and red. The architects drew inspiration from the Thunderbird series, and this shows in the eye-catchingly futuristic final product; each module is elevated on its own four stilts, giving the impression it has recently touched down from another planet. The inside of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) station is reserved for science, but on the outside, spectacle reigns.

Halley VI became operational in 2012, and was designed specifically to be able to cope with the movement of the Brunt Ice Shelf, annual snowfall of 1.5m, and the problems associated with snowdrift. Hydraulic legs provided the ability to lift the modules above any drifting snow, and the modules were mounted on skis for ease of transportation. That design was put to the test this summer, when the station was moved 23km to a new location known as Halley VI a. With a growing ice chasm threatening the station’s initial location, relocation became pressing; scouting was undertaken during the 2015/16 season followed by a complete move involving the cancellation of the 2017 winter season. This physical shift is indicative of a conceptual shift in how Antarctic stations are conceived. Aside from offering protection from the elements, they now need to be able to respond to the environment and to engage the public imagination.

This is not the first time Halley VI has made headlines. When it was commissioned, the station was also in the spotlight, not least because of its eye-catching design. An architectural competition was held in 2004, and the brief was comprehensive. The station was required to be fully relocatable, have a low environmental impact, the ability to deal with annual snowfall, and be a safe and comfortable environment for up to 52 scientists who would call it home. The harsh Antarctic environment presents particular challenges, from climatic (low temperatures, strong winds, moving ice, low humidity, heat dissipation) to logistical (remoteness, communications, access, transient population) to psychological (isolation, sensory deprivation). Environmental protection must also be taken into account, and a Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation prepared, making any Antarctic build a complex process.

The competition to design the station also offered a novel way of engaging the public with Antarctic science; BAS used “the quest for a new building to raise awareness and engage public interest in the vital scientific work being carried out in Antarctica.”[1] The hope was that media coverage of the new build would also include information about ongoing research programmes and their outcomes (such as the discovery of the ozone hole at Halley in the 1980s), as journalists and the public asked questions about the role of such stations and Britain’s Antarctic presence. In celebration of the new build, a special postage stamp series was also released, as well as a £2 commemorative coin. Britain is one of 7 “claimant nations” in Antarctica and considers Halley VI to be located in the British Antarctic Territory, which adds another motivation to keep Antarctica alive in the minds of the public.

Hugh Broughton Architects were awarded the contract for Halley VI, a concept that has been described as signalling “a new dawn for 21st Century polar research.” Their design has gone on to win several architectural awards since the build took place, including the RIBA International Award 2013 and several sustainability accolades. The firm has also pitched designs for several other Antarctic stations in recent years, including Korea’s Jang Bogo Station (2010) and Brazil’s Comandante Ferraz Station (2013). Both the Korean and Brazilian builds went to other companies, but Hugh Broughton did win the tender for Spain’s Juan Carlos Station (2007). This is a trend to watch in the future as specialist architects emerge with the ability to tender for Antarctic builds on a regular basis; other firms with a proven Antarctic record include Ferraro Choi (USA’s Amundsen-Scott Pole Station) and IMS Ingenieurgesellschaft (India’s Bharati and Germany’s Neumayer stations). Such designs could also provide models for future buildings on other planets.

How did we get to this point where futuristic modules on stilts and skis provide a home for Antarctic scientists and support personnel? As architect Sam Jacob puts it, “the history of Antarctic architecture seems a hyper-accelerated history of architecture itself, progressing from the hut to the space station in just over a hundred years.”[2] The challenges associated with living in the Antarctic have been addressed in a number of ways over that time, and architecture has played an important role in developing solutions and building on past successes. As Hugh Broughton architects explain, the entrances in their design, which are specifically created to keep out the wind and ice, “stemmed from 50 years of designing doors in the Antarctic.” The design also drew on developments pioneered by other National Antarctic Programmes, as well as lessons learned from the past five incarnations of Halley.

Halley I in 1956-57. (Photographer: unknown; Archives ref: AD6/19/3/C/Z6)

Like many Antarctic stations, Halley I was first established in 1956 as part of the International Geophysical Year. The initial station consisted of simple wooden huts built directly on the ice. This proved to create issues with the drifting snow as the buildings were slowly buried. New additions were eventually added on the surface, creating a multi-level structure that reached beneath the ice. This caused its own problems, low temperatures being a big concern. The station was buried beneath 14m of snow and ice by the time it was abandoned in 1968, in favour of Halley II.

Halley II in 1967 (Photographer: Maurice Sumner; Archives ref: AD6/19/3/C/Z25)

Halley II (1967 – 1973) was built with the challenge of drifting snow in mind. Although it was also built directly on the ice, the second iteration of the station featured steel-reinforced roofing to cope with the weight of the snow. Unfortunately, the steel proved no match for the Antarctic ice; the station was only operational for 7 years. A new approach was needed.

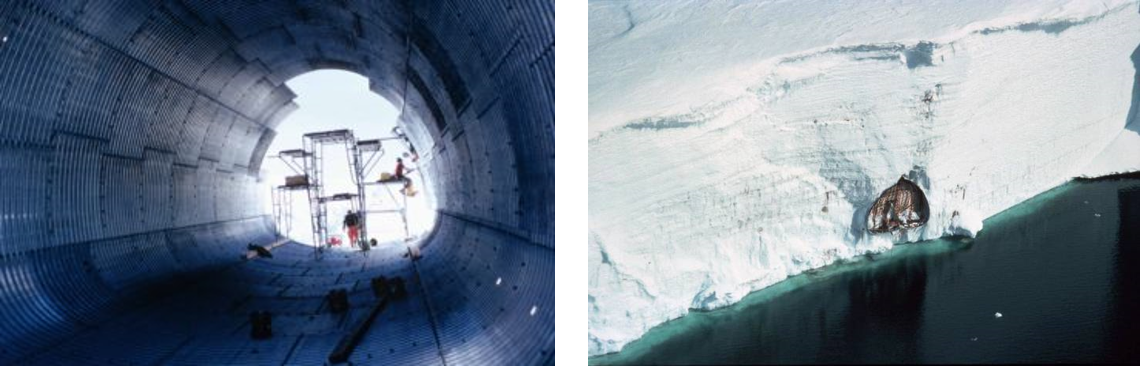

Halley III in construction in 1973 (Left) (Archives ref: AD6/19/3/C/Z38). Photographer: Vivian Fuchs (Director, FIDS) and Halley III in an ice cliff in 1993 (Right)(Photographer: Andrew Alsop)

Halley III (1973 – 1984) took on the challenge posed by burial by placing wooden huts inside long corrugated steel tubes which were designed to be covered by the snow and withstand the pressure. While the concept worked initially, it also revealed further issues, namely with insulation; heat escaped from the buildings and caused the surrounding ice to move faster than expected, distorting the protective structure. Halley III was eventually crushed, and emerged from the Brunt Ice Shelf several years later encased in a calving iceberg.

Halley IV in 1983 (Archives ref: AD6/2Z/1983; Photographer: Doug Allen)

The lessons learnt were applied to Halley IV, however, this time interlocking plywood panels were used for the tube shape, complete with specially designed insulation gaps. Unfortunately the wood was warped by the winds, reducing the effectiveness of the cylinder shape, so snow had to be cleared from the roof on a regular basis throughout its life. The unexpected challenges that come when translating theory in to practice in a harsh environment are difficult to control.

Halley V

Halley V (1991-2012) looked very different than its predecessors. Rather than combating snow-drift through burial, the station was elevated on stilts so it sat 4m above the surface of the snow. The legs could be independently adjusted by a team of welders, allowing for corrections in height and for any distortions caused by moving ice. The elevation solution has also been employed by many other nations, both on the ice and on a rock base; South Korea’s Jang Bogo Station, China’s Kunlun Station and the joint French/Italian Concordia Station are but a few examples. For Halley V, the design was so successful that durability proved the reason the station needed to be replaced. With the Brunt Ice Shelf moving towards the sea, there was a growing risk of losing the station in calving event. It was this realisation that led to relocation capability being specified in the design brief for Halley VI.

Halley’s history is indicative of trends across Antarctica. Stations have been built on grade, under the ice, on stilts, and using a combination of techniques. Such a trajectory is common for stations that are built on ice, as they must be rebuilt periodically; the US Scott-Amundsen South Pole Station was first built on grade during the IGY, and now stands elevated, while Germany’s Neumayer Station has existed on grade, in tunnels, and on different types of stilts. Other stations, particularly those built upon rock, have been renovated over the years, adopting new advances as they became necessary.

Architectural design is now an important element when it comes to building new Antarctic stations. As Sandra Ross points out in her introduction to the ‘Ice Lab’ Antarctic architecture exhibition, “it was only until recently that the mainstay of Antarctic Architecture was based purely on function; now, however, the region is a forum for design, technology and innovation.”[3] New stations are not only shelters for those who travel south, but also flagships for their respective National Antarctic Programmes. They are a way of drawing attention to a nation’s presence in the Antarctic, as well as its polar research. Examining the history of Britain’s Halley Station reveals much about such advances in engineering and architecture; to look back at the various incarnations of Halley is to trace the evolution of the Antarctic station, from functional shelter to architectural showpiece.

This article draws on material published in a 2014 report for the Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programmes (COMNAP), entitled “From Shelter to Showpiece: The Evolution of Scientific Antarctic Stations”

[1] Malcolm Reading, “Foreword” in Halley Research Station Design Concept Competition: Supporting Documents, British Antarctic Survey. Available via https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/18030284/british-antarctic-survey-netzentwurfde/3

[2] Sam Jacob, “High Tech Primitive: The Architecture of Antarctica,” in Ice Lab: New Architecture and Science in Antarctica. eBook. 2013. www.artscatalyst.org/projects/detail/e-book_ice_lab/

[3] Sandra Ross (ed.), “Introduction,” in Ice Lab: New Architecture and Science in Antarctica. eBook. 2013. http://www.artscatalyst.org/projects/detail/e-book_ice_lab/