Land-based activities are a specialised and niche part of Antarctic tourism, which have received relatively little attention in policy and academic circles. While a small proportion of tourists engage in these deep-field and continental activities, it poses an outsized risk, both to the environment and the politics of Antarctica’s governance. This article analyses land-based tourism, discusses its (lack of) regulation and suggests that it should be seized upon as a useful form of infrastructure on the white continent – provided it is effectively managed.

What is land-based tourism? One of the few definitions is offered by Bastmeijer et al. (2008), who consider it a form of tourism, “that makes use of facilities on or connected to Antarctic land or ice”[1]. (And given almost all ice in Antarctica lies on the continent itself, we’ll assume ‘ice’ means ‘land’ here). The first land-based facilities designed for tourist purposes were constructed in 1982 for delegates at an annual conference at the Chilean research station Teninente Rondolfo Marsh on King George Island[2]. This lasted until 1993, but US-based Adventure Network International (now part of Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions; ALE) developed a blue-ice runway in 1986, allowing for the first time private air access to the continent’s interior.

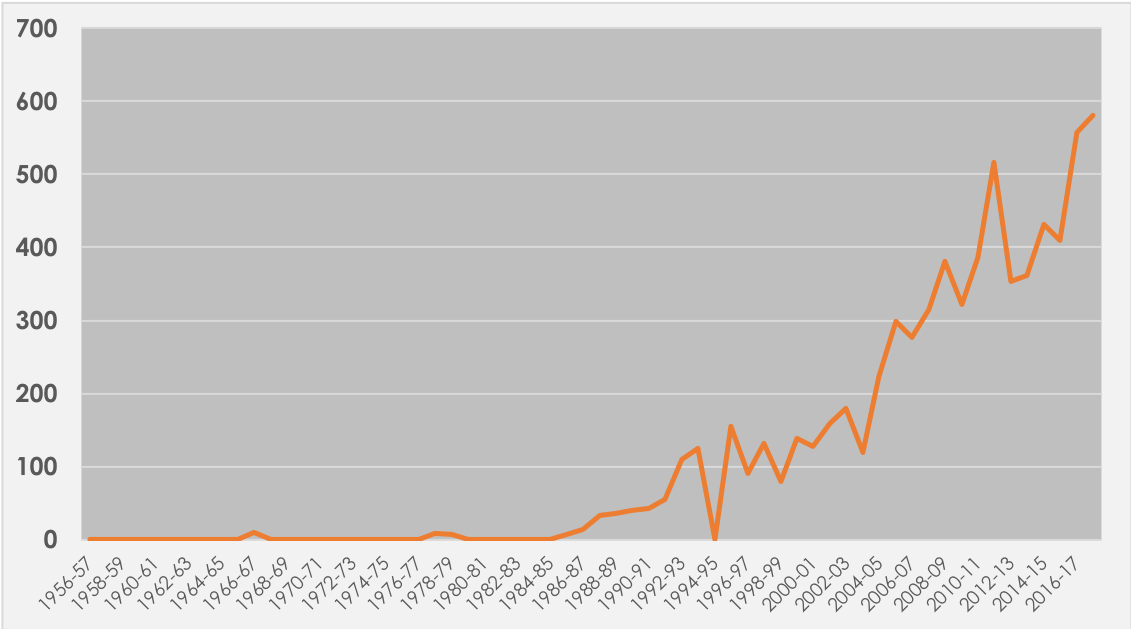

The industry has since developed slowly and is now concentrated among a small group of companies. White Desert, based in the UK, ALE (US), and The Antarctic Company (South Africa) served 580 tourists in 2017-18, around 1.1% of total arrivals[3], with activities on offer including camping, skiing, snow-shoe walking and mountaineering. While it has grown significantly over the last 20 years (Figure 1), it remains a niche part of Antarctic tourism practised by those lucky enough to reach the continent’s interior. That should not discount its relevance, however, as will be discussed.

Figure 1: Land-based tourist arrivals in Antarctica (Source: IAATO).

As with any activity, this form of tourism will pose some risk to the local environment. Article 3 of the Environmental Protocol outlines how all activities in Antarctica, whether government research projects or tourist visits, must undergo checks before they can proceed: an Initial Environmental Evaluation (IEE) for those with a ‘minor or transitory impact’ on the environment[4], or a Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation (CEE) if there could be a greater impact. These are registered with the relevant national authorities, who would then give permission for the activity to take place. Both IEEs and CEEs are published annually, indicating publicly the level of activity taking place. Adventure tourism itself does not have often have a significant environmental impact. A small group of mountaineers should cause less damage than 100 pairs of feet on the Antarctic coastline, and registered activities have hitherto met the required environmental standards.

Of greater concern are other aspects of land-based tourism. These activities are riskier than straightforward cruise visits, often taking place in harsh, remote environments away from search and rescue centres. They require more careful management and expertise, which is emphasised in the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators (IAATO) guidelines specific to land-based tourism. Another issue for some authors is that tourists are there for their specific activity and may not share the Antarctic ‘values’ emphasised by national and private organisations, such as respect for the continent’s environment, fragility and its wilderness[5]. The importance of Antarctica to both scientific and conservation efforts is therefore less likely to spread through ‘Antarctic ambassadors’.

The environmental-review process raises questions about definitions. The blue-ice runways of White Desert and ALE are deemed semi-permanent, despite their re-emergence each season[6]. In the context of Antarctica, where tourism is almost entirely seasonal, it could be considered as effectively permanent. This is not without implications, as the Australian Antarctic Division – which operates a blue-ice runway at Wilkins station – has proposed the construction of a new, paved runway to expand their logistics capabilities at Davis station[7].

Building infrastructure, whether permanent or temporary, involves some form of ownership by the respective firm. While this property right is guaranteed by the relevant national authority, it does not extend to the ground beneath the facility, as under Article IV of the Antarctic Treaty, no sovereign claims are recognised in Antarctica. But there is a certain expectation of exclusivity: no firm operating, for example, a camp would want another firm (or national programme) operating in the immediate area, not least because of the cumulative environmental stress. It becomes, in effect, a property right. With the high concentration of firms based in established Antarctic states (such as the UK and US), these will enjoy effective jurisdiction over an expanding area of Antarctic space. Verbitsky argues this even poses a threat to the Antarctic Treaty system itself[8]. At current levels of land-based tourism, this is an exaggeration, but is certainly a possibility as facilities expand and spread. The political risks are the most serious, and this is where regulation will prove necessary to alleviate such concerns.

Figure 2: Gulfstream landed in Antarctica (Source: White Desert).

Despite these risks, the small scale of land-based tourism has allowed it to escape much regulatory attention. Awareness was drawn for the first time only at the annual Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting in 2004, when New Zealand argued it should be prohibited. States have since offered conflicting views, where the Netherlands and New Zealand especially have called for more regulation – including outright bans[9]. Others, such as the UK, have suggested a precautionary and more strategic approach[10]. Overall, there has not been much engagement, and no real agreement when mentioned: even the UK’s suggestion of a non-binding Resolution to limit non-governmental infrastructure in 2006 was not adopted.

Land-based tourism is therefore lightly regulated, only subject to laws imposed under the Environmental Protocol. This is interpreted on a national basis, with firms having to secure permits in a process that varies enormously in scope, detail and timing[11]. The IAATO, a member-led organisation tasked with promoting safe and environmentally responsible private-sector travel, considers this problematic[12], not least because it encourages ‘forum shopping’. In response, it developed its own set of regulations, the core of which was adopted by the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties (ATCPs) as Recommendation XVIII-1 in 1994[13]. These include protecting Antarctic wildlife, respecting protected areas and scientific activities, keeping safe and maintaining the wilderness nature of the local environment[14]. Further objectives have been specified for land-based tourism, including having sufficient medical experience and informing local National Antarctic Programmes of their planned activities.

The system reflects a faith in the IAATO, but also, more seriously, a general inability to reach consensus at state-level meetings[15]. The resulting lack of regulatory oversight means that new and innovative forms of tourism – involving new technologies and facilities, or adventure activities such as skiing – may develop and spread without checks to prevent risks to the environment or safety. This form of tourism is likely to continue its upward trajectory, with the Adventure Travel Trade Association reporting the growth in adventure tourism at around 21% per year[16]. Environmental and resource pressures in Antarctica could be compounded by political risks to the Treaty system.

Land-based tourism occurs on a small scale with little environmental impact, taking place among a small group of specialised firms with expertise appropriate to the risks involved. Moreover, the firms provide additional logistics and search-and-rescue capabilities to public research programmes: White Desert and ALE both operate blue-ice runways also used by National Antarctic Programmes, while The Antarctic Company is the commercial arm of Antarctic Logistics Centre International, involved in the Dronning Maud Land Air Network that sees numerous states share air-transport capacity. The managed proliferation of private airbases would facilitate a network of air-access points, fostering scientific access and search-and-rescue capabilities without draining public funds. Establishing an international Antarctic tourist body to work in partnership with IAATO would alleviate concerns over environmental impact by allowing close control of construction. There is a chance to be proactive about land-based tourism.