Introduction

The beginning of the year 2023 was marked by a ‘spectacular find’ (Der Spiegel, 2023) in Northern Sweden: rare earth metals. This find made headlines all over the world (Aftonbladet, 2023; Bye, 2023; Chatterjee, 2023; Die Zeit, 2023; Donges, 2023; Frost, 2023; Hivert, 2023; Masih, 2023; Nielsen, 2023; Petrequin, 2023; Reid, 2023: Reuters, 2023; Sternlund, 2023; Sullivan, 2023; Sunazes, 2023), which, as we will see, is considered as a major step to gaining resource-independence from China. What is largely missing from the reports is a long-lasting problem that has accompanied resource extraction, especially mining and tourism, for decades in Arctic Scandinavia: clashes with the indigenous Sámi who have lived on, used and owned these lands for thousands of years.

In this contribution, I will present the framing of the find as presented in widely accessible news outlets from all over the world, bearing particular attention to the major foci of the articles. What is notable is the fact that neither in English-speaking media outlets from Russia and China, i.e. TASS, The Moscow Times and Global Times, nor in Japanese outlets, any mention of the find can be found. It consequently appears that this is primarily a Western, if not European, issue.

The find

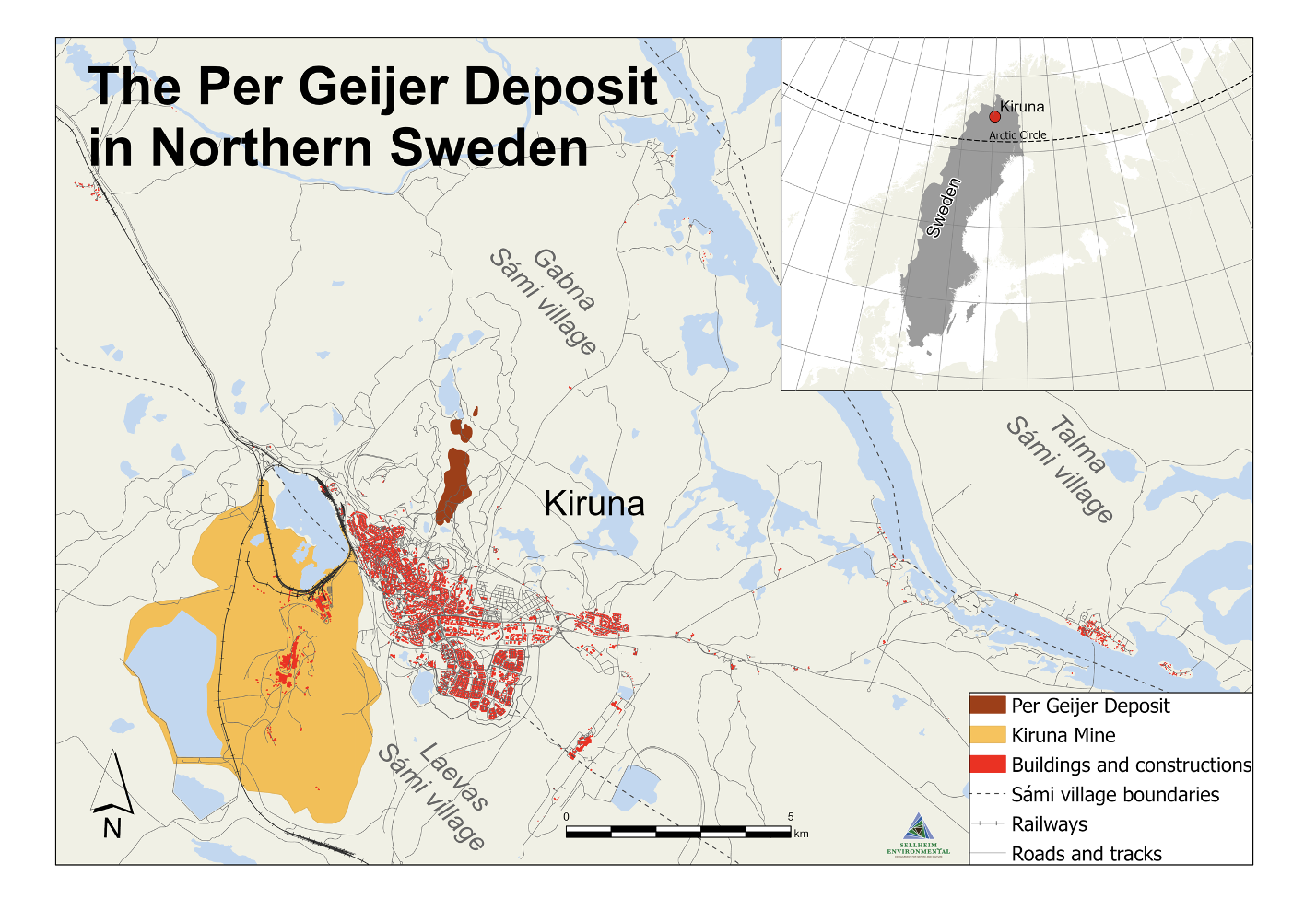

On 12 January 2023, Swedish state-owned mining company LKAB announced that it had discovered one million tonnes of mineable rare earth metal oxides in the Kiruna area, far above the Arctic Circle. The so-called Per Geijer Deposit is therefore the largest deposit of rare earths in Europe, which, according to LKAB’s CEO Jan Moström, “are absolutely crucial to enable the green transition” since “[w]ithout mines, there can be no electric vehicles” (LKAB, 2023).

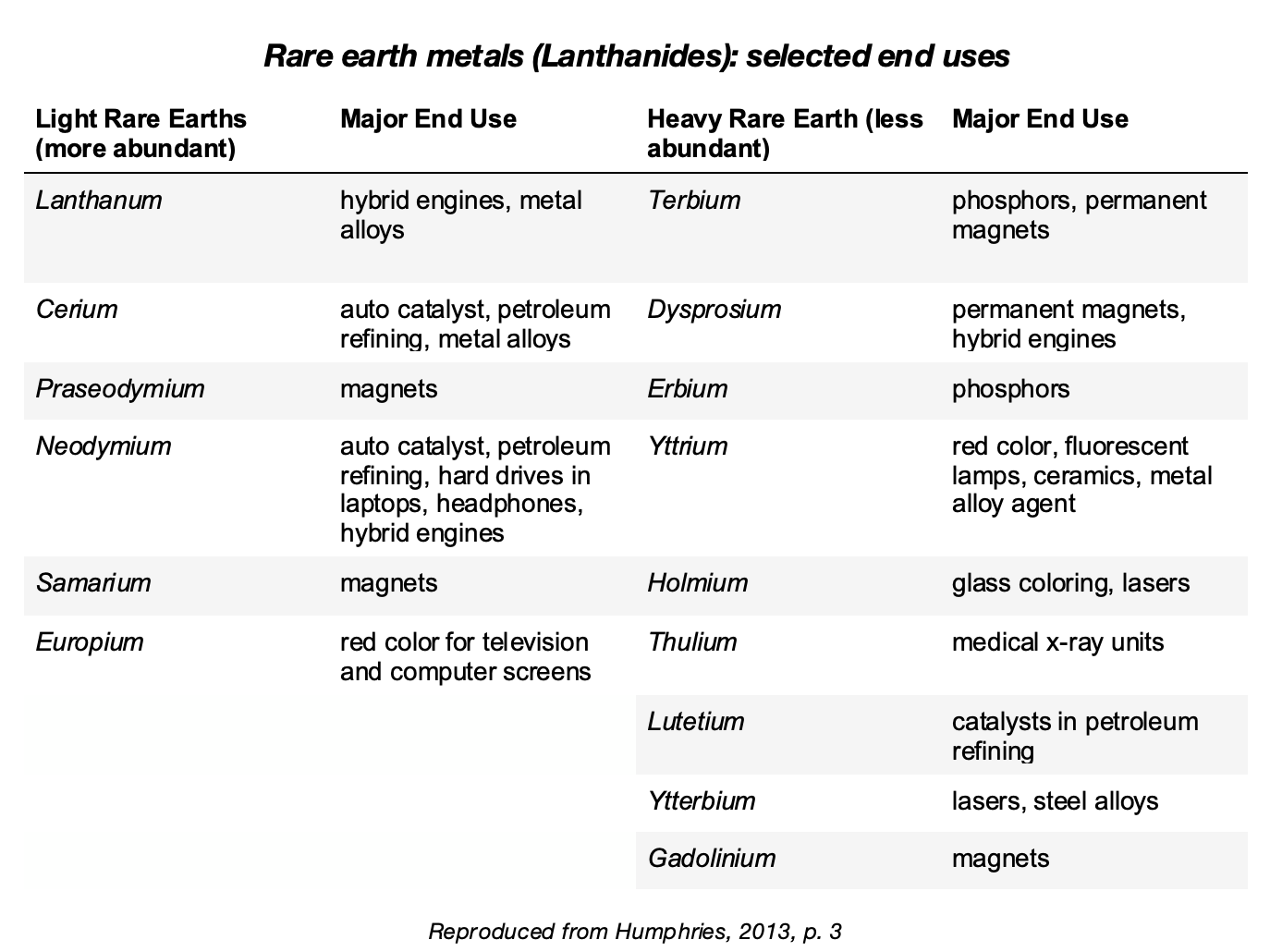

Rare earth metals are a group of 17 elements from the periodic table which, due to their unique characteristics, are primarily used for the production of high quality magnets, alloys, ceramics and other parts crucial for electronics, such as smartphones. Moström’s statement, however, refers to their uses in the production of magnets for electronic vehicles and wind turbines, both of which are considered elementary for the green transition. In Germany, especially the latter has become a major issue for the generation of energy after the country has taken its last three remaining nuclear power plants off the grid on 15 April 2023 (Federal Office for the Safety of Nuclear Waste Management, 2023).

The rare earths deposit consequently allows for the conclusion that Sweden and Europe now possess free access to a key element for the green transition, a cure for rising temperatures resulting from anthropogenic climate change and providing future generations with a path to a greener future. Numerous news outlets have taken up this narrative by LKAB’s CEO or reproduced his statement verbatim (Bye, 2023; Masih, 2023; Reuters, 2023; Sullivan, 2023; Petrequin, 2023; Reid, 2023).

Indeed, also the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, remarked in her 2022 State of the Union address that “Lithium and rare earths are already replacing gas and oil at the heart of our economy” (von der Leyen, 2022) – a statement which also politically, not only economically, increases the role of rare earths in Europe.

From a political and furthermore geopolitical perspective, the discovery of the Per Geijer rare earths is indeed a rather huge step. After all, the de facto monopoly on the production of and international trade in rare earths rests on China, which factually uses its international standing for geopolitical purposes (Kalantzakos, 2017). While, of course, also the abundance of oil and gas is geographically limited with significant geopolitical and economic implications (the best example probably being the exploding energy prices in Europe after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine), there are nevertheless alternatives and the more diversified the energy sector is, the better it can absorb shocks. This is not the case with rare earths.

Geopolitics and free trade

Rare earth metals play a crucial role in the world’s societies and have catapulted China to the top of their global distribution within the last 20 years or so. But only towards 2011, the geopolitical implications of rare earths have entered public discourse when China opted for a tightening of rare earth exports, leading to skyrocketing prices. Of course, this did not go unnoticed (Fan et al., 2022). Quite generally, however, a higher geopolitical risk translates into high prices for rare earths, making them consequently very susceptible to the developments worldwide (ibid.).

When taking into account the currently stable, but not necessarily solid, relationship between the West (or the European Union) and China, it is not surprising that the find in Kiruna is considered a major step towards resource independence from China and a contributor to Western/European economic stability, given that Europe consumes around 30% of the world’s rare earth metals. Production, it seems, is coming home. This narrative is transported by virtually all articles under scrutiny. Against this backdrop, it is not surprising that the (English-language) Chinese media do not report about the find since it has the potential to strip China of some of its geopolitical and economic power. Given China’s rise over the last two decades or so, it indeed silences a screaming superpower to some degree.

In this regard, however, merely one article, which includes a short interview with Finland’s former prime minister Alexander Stubb, presents a somewhat critical view on the matter. As Stubb’s remarks show, the find could also lead to more tensions between the EU, China and the USA, given that it has the potential to decrease Sweden’s and the EU’s ability to engage in open trade. Stubb, therefore, remarks that “we need export and we need open trade” [“vi behöver export och vi behöver öppen handel”] — something that the current find undermines (Sternlund, 2023).

At present, it still remains to be seen what kind of geopolitical implications the find will have. After all, the exploitation of the discovered rare earth metals will not be done in the near future, but will still take another 10—15 years. As Russia’s rather sudden invasion of Ukraine has shown, much can happen within this time span.

The longest screams by the indigenous Sámi

A major blind spot in most of the articles under scrutiny are the implications of the find on the livelihoods of the indigenous Sámi, whose traditional lands span over northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. For decades, they have fought for a recognition of their rights and culture(s). Norway is the only country which has ratified the legally-binding ILO Tribal Peoples Convention No. 169, while Sweden, Finland and Russia have merely signed the non-binding UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Leaving the situation of the Russian Sámi aside — after all, the conditions are significantly different to the Nordic countries — in Sweden and Norway, reindeer herding, an important marker for Sámi culture, is an exclusive right of the Sámi, whereas in Finland it is not.

Reindeer herding has been subject of various legal cases before national and international tribunals. One of the most prominent cases in Sweden is Kitok v Sweden (1985) before the Human Rights Committee, overseeing the International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), dealing with the interpretation of the ICCPR’s Article 27 on the rights of minorities. Without the need to delve into more detail here, suffice it to say that in the Nordic countries land use has been a major element of conflict between reindeer herders and other economies for decades, having generated a huge body of academic literature (for a recent contribution, see Cambou et al., 2022).

In Sweden, reindeer herding is regulated using the concept of samebyar (Sámi villages), which essentially follow the traditional migratory routes of the animals. They also constitute administrative boundaries within which reindeer herders conduct their husbandry. Since reindeer require large spaces, a reduction in this space and changing ecosystems due to climate change inevitably lead to problems for the reindeer and thus the herders. And this is where the new find comes in.

Amongst the scrutinised articles, merely three (Frost, 2023; Hivert, 2023; Nielsen, 2023) refer to the threat the mine poses for the Sámi, and especially the Gabna Sámi village (leaving aside several articles in the Swedish media). Given that the town of Kiruna, associated urban development and the large mine have already taken up significant swathes of land in a section of the Sámi village which is already quite narrow, the Per Geijer deposit furthermore decreases this corridor, making it difficult for the reindeer to migrate through — essentially dividing Gabna Sámi village into two parts, as its spokesperson Karin Qvarfordt Niia laments (SVT Nyheter, 2023). Not surprisingly, the mining operations are considered a major threat to the Sámi village and sustainable reindeer herding. In an interview as part of a short report on the find in the German Europamagazin, Anders Lindberg, a spokesperson of LKAB, however, dismisses these concerns and stresses the need for sacrifices everybody has to make in order to tackle climate change (Europamagazin, 2023).

While there are some media sources which do take note of the concerns of the Sámi, most do not. Those that do largely fail to recognise the decade-long struggle of the Sámi over their traditional lands. The long screams of the Sámi for their rights is consequently silenced by the way the rare earths find in Northern Sweden is communicated.

Conclusion

The above has shown that the primary narrative of the articles under scrutiny circles around resource independence from China. While no direct evaluation is given, the reproduction of LKAB’s views makes it difficult to form different opinions, as that presented in Sternlund (2023). In so far, I dare to say that a rather one-sided picture is generated that is infused with political underpinnings as the State of the Union by Ursula von der Leyen demonstrates.

With regard to the Sámi, it is almost impossible to find references to their struggles in the majority of news sources. This shows how little their concerns have found their way into mainstream reporting — an issue that should raise eyebrows amongst the general public and decision-makers. Arguably, this indicates that their concerns are not considered important enough to be reported about, but that, especially in light of the ongoing war in Ukraine, geopolitical and economic issues, which also concern ‘us’ trump those issues which only concern ‘them’ (the Sámi).

Especially the latter demonstrates that we are still a long way from a mainstream recognition of European colonial past and present, which also extend into the northernmost reaches of the European continent. Whether this will change eventually remains in the realm of speculation.

Media articles

Other sources