Introduction

Whaling in 2023 still constitutes an activity of utmost controversy. While the 88-member state International Whaling Commission (IWC) has put in place a ban on commercial whaling in 1982 that came into force in the Antarctic whaling season 1985/86, this does not mean that whaling per se is illegal throughout the world. First of all, the so-called ‘moratorium’ is only relevant for those states that are members of the IWC and, amongst those, binding only for those that have not lodged an objection to it. In practice, that means that both Norway and Iceland — the latter left the Commission in the early 1990s, but rejoined it in 2002 with a reservation towards the moratorium — still conduct commercial whaling, despite being IWC members. In four IWC member states, IWC-regulated Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling (ASW) is still conducted for subsistence purposes: in the United States (Alaska), Greenland, Russia (Chukotka) and St Vincent & the Grenadines (Bequia).

Since the moratorium has come into force, it has been one of the most controversial decisions ever taken by the IWC and has led to antagonistic positions within the Commission: on the one side are countries that oppose commercial whaling vehemently; on the other side are states either directly whale or that support the principle of sustainable (lethal) use of whales for principal reasons, also as a potential source of food in the future. The spearhead of the latter group has been Japan, which has fought for a resumption of commercial whaling for decades. Since Japan’s initiatives have been fruitless, the country left the Commission on 1 July 2019 and is now able to conduct commercial whaling within its 200nm Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) outside of the control of the IWC.

Although whaling is no longer as industrial an activity as compared to the past, it still faces major resistance within the Commission, but also in media discourse. For instance, the dramatic hunt of approximately 1,400 Atlantic white-sided dolphins in the Faroe Islands in 2021 made headlines all over the world (Sellheim, 2021). While legal (the IWC only regulates whaling of ‘great whales’, excluding small cetaceans such as dolphins), it is often portrayed as inherently cruel, unsustainable and, depending on the source of information, illegal.

At the end of August 2023, several media sources reported that whaling has resumed in Iceland after a hiatus of two years between 2019—2022 and a suspension of licences in 2023 over animal welfare concerns; commercial whaling for fin whales has now resumed. In Japan, in the small village of Taiji, the whaling season has also begun. Here, it is especially small cetaceans that are hunted outside the ambit of the IWC, but under the watchful eye of the public: along with several anti-whaling protestors, activist Ric O’Barry travelled to Taiji in August 2023 to protest whaling. O’Barry has gained fame by starring in the (documentary) film The Cove in 2008, which portrayed Taiji whaling as cruel and unnecessary, and which came to be an Academy Award winner (Psihoyos, 2008).

Recent media coverage of Icelandic and Taiji whaling

Icelandic whaling

While not overly prominent, several international news outlets have reported about the resumed hunts in Iceland and Taiji. The Guardian, France24, BBC, Etelä-Suomen Sanomat, MTVUutiset, Aftenposten and Der Spiegel report that despite a whaling ban that lasted for approximately two months in the summer of 2023, whaling has now resumed ‘under strict rules’ with regulations in place that improve animal welfare standards in whaling (Aftenposten, 2023; Der Spiegel, 2023a; Etelä-Suomen Sanomat, 2023; France24, 2023; Kirby, 2023; McVeigh, 2023; MTVUutiset, 2023). In all articles, Iceland’s Minister of Food and Agriculture, Svandís Svavarsdóttir, is cited as not seeing a reason to further suspend whaling given that the licences were issued before she started her tenure and that whaling practices are now following stricter animal welfare rules.

When Svarvarsdóttir issued the suspension of whaling in June 2022, several news outlets reported about this decision, hailing it as a (partial) victory for animal welfare and rights groups (Euronews, 2023), especially since the Minister remarked that whaling has no future in Iceland (if animal welfare standards are not met). It is especially the way this statement was interpreted by news outlets, which is interesting to consider: While in Euronews (2023) Svarvarsdóttir is quoted has having said that “whaling has no future”, in AlJazeera (2023), the full quotation is presented: “If the government and licensees cannot guarantee welfare requirements, these activities do not have a future.”

Most of the reports about Icelandic whaling cite animal rights and welfare groups who express their disappointment over the recent resumption of whaling. Der Spiegel quotes a representative of the organisation Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC) (Der Spiegel, 2023a); France24 and Aftenposten mirror the disappointment of the head of the Humane Society International (HSI), Ruud Tombrock; The Guardian includes the views of representatives of the WDS, HSI and the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), while the BBC reflects the foresight of a representative of IFAW that “this year will be the final year of whaling in Iceland” (Kirby, 2023).

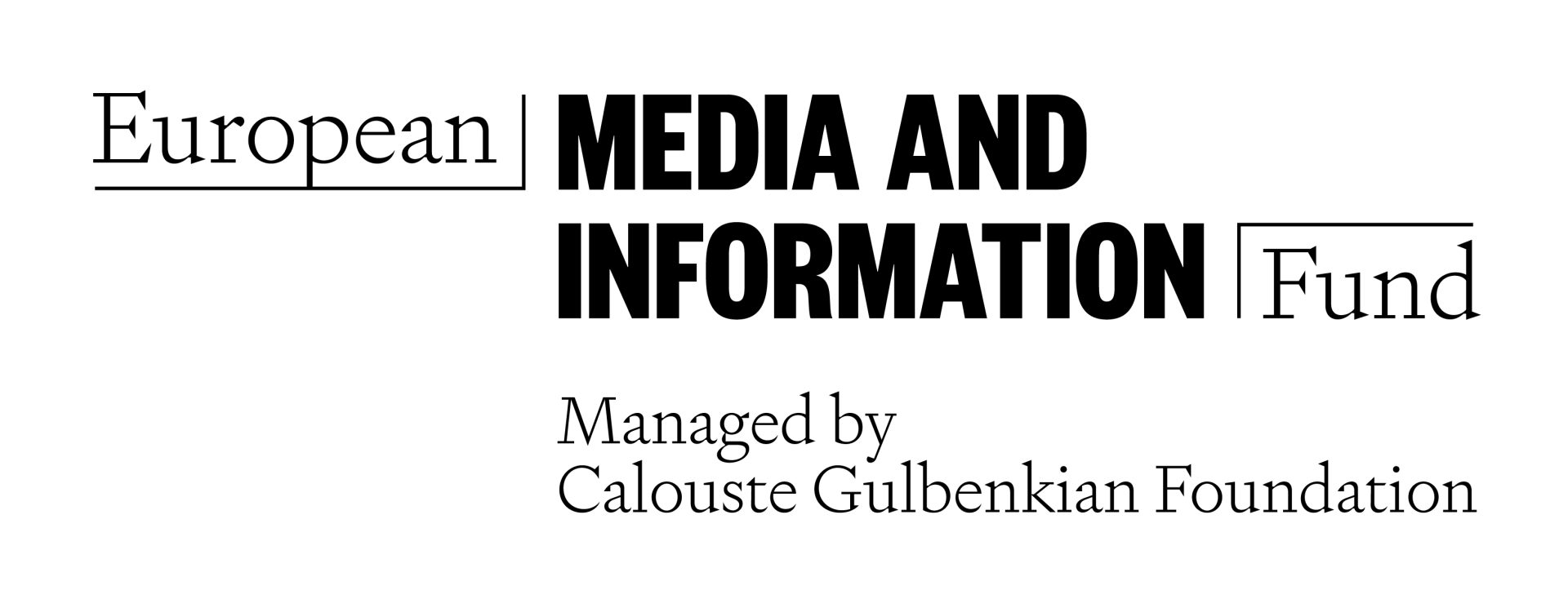

The latter statement is rooted in a recent poll carried out by the Icelandic Maskina Institute that showed that opposition to whaling has grown from 42% to 51% over the last four years (RFI, 2023). Even though the survey does not seem to be publicly available, and despite the fact that the result means that 49% of Icelanders are still in favour of (or at least indifferent to) whaling, the news outlets under scrutiny here value the results as proof that also within Iceland, whaling no longer finds support. Indeed, one of the most prominent Icelandic celebrities, the singer Björk, has also started to campaign against Icelandic whaling on Facebook, going further to lead a protest against whaling in Reykjavík in June 2023.

Whether or not public and/or political pressure on Icelandic whaling will increase in the future remains to be seen. Celebrities such as Björk and actor Leonardo DiCaprio (Der Spiegel, 2023a) act as conduits for an anti-whaling voice, BBC notes, quoting Katrin Oddsdottir of the Icelandic Nature Conservation Association that “there was a genuine risk of a Hollywood boycott of Iceland now that the practice was being allowed to resume” (Kirby, 2023). A Hollywood boycott is consequently used as a threat towards Iceland’s decision-makers to end whaling.

A similar mechanism was used in the past, albeit from the highest US government level: in 2014, for instance, Barack Obama issued a Memorandum in which he supported Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell’s certification of Iceland under the so-called ‘Pelly Amendment’ of the Fisherman’s Protective Act of 1967, which allows the Secretary to certify nationals of a foreign country who are engaging in trade which diminishes the effectiveness of any international program for endangered or threatened species. This certification allows the President to move Congress for any concrete action to ensure the conservation of the species. After Iceland had resumed fin whaling in 2014, such a certification occurred over the diminishing of the effectiveness of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) since Iceland started to engage in international trade in whale meat. In the Memorandum, Obama instructed his Cabinet and the different ministries to take soft action, thereby putting pressure on Iceland to rethink its decision (Obama, 2014).

What several of the articles wrongly state is that Iceland, along with Norway and Japan, is the only country in the world in which whaling is still conducted (AlJazeera, 2023; Kirby, 2023; MTVUutiset, 2023; Etelä-Suomen Sanomat, 2023; RFI, 2023). Merely Der Spiegel (Der Spiegel, 2023a) and Aftenposten (Aftenposten, 2023) correctly note that these countries are the only ones in which whaling is still commercially conducted. The introduction to this article already shows that ASW is conducted in four regions of the world. Beyond that, however, whaling still occurs in Canada and Indonesia (Bock Clark, 2019).

Taiji whaling

The start of the whaling season in Taiji in 2023 has found significantly less media coverage than the resumption of whaling in Iceland. Der Spiegel notes that “Japan slaughters dolphins again” (“Japan metzelt wieder Delfine”; Der Spiegel, 2023b), while the same narrative can be found in Teller Report (2023). In fact, the newspaper reports about the Taiji whale drive every two years on average. This year, Taiji whaling has found almost no media reflection outside of Japan. In early 2023, several news outlets reported about Taiji: Newsweek presented a commonly found overview of the hunt (Whyte, 2023), while The Guardian reported about a complaint by an Australian animal welfare group, Action for Dolphins, about the level of mercury in dolphin meat and that it be removed from sale (McCurry, 2023). Also, non-governmental organisations still working to end the Taiji whale drive have published and distributed articles underlining their opposition to the practice (Matthes, 2023; Rosenberg, 2023). Compared to the media coverage of the years before and to the coverage on Icelandic whaling, Taiji is covered relatively a little in current media coverage.

The Taiji whale drive © Nikolas Sellheim, 2018.

The Taiji whale drive © Nikolas Sellheim, 2018.

Research carried out in Taiji by the author in 2017 revealed that the ‘most significant change’ — a method developed by Rick Davies in 1994 and applied during fieldwork — that occurred in the village was the moratorium on commercial whaling and the release of The Cove. Both events affected the community significantly: the former, because villagers were not able to process and consume meat from ‘great whales’ anymore. While the consumption was not high, humpback whale meat nevertheless played an important role in the diet of the region. However, the moratorium also affected the village in such a way in so far as Taiji whalers were very experienced. Since the Japanese government initiated the JARPA research whaling programme in 1987, whalers were needed on the vessels in the Southern Ocean. To this end, many Taiji whalers were recruited who then spent several months away from their families. Inevitably, the socio-economic dynamics within the community changed quite fundamentally.

The Cove affected the community by putting it on the world map and by sparking controversy and outrage amongst outsiders. Because of protesters, the community started to shield itself from outside influence, and every foreigner — including the author — is met with suspicion. Also, the small police station that can be found next to ‘the cove’ was built solely to keep foreign protesters under control. The main grocery store in the community is monitored, and photos are prohibited. While protests were soaring shortly after The Cove, these ebbed down over time, but recently have seen a resurgence. While the Sea Shepherd-run ‘Cove Guardians’ do not appear to exist anymore, the constant resurfacing of the hunt in the media point towards a still existing interest in the whalers and their activities.

What is hardly understood is that Japanese ethics towards animals differ from ‘Western’ ethics. On the one hand, animals such as whales are killed. On the other hand, they are worshipped as contributing to a community’s sustenance (Itoh, 2018). In Taiji, whales play even a different role. Virtually in every corner of the community, images or sculptures of whales are found, and the lighthouse has a whale-shaped wind rose at its top. The long whaling history is probably best shown in the different shrines that worship whales in the entire Wakayama region, as well as by the carved rock that can be found on the beach, done by a mason who was tasked to carve the rock by a whaling captain for unknown reasons.

At the centre of Taiji’s whaling history stands the Taiji Whale Museum. While showing the rich history of whaling in the region and providing information about whales themselves, it also holds a sea park and an aquarium. In both, small cetaceans such as false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens), common dolphins (Delphinus delphis) or different species of pilot whales (Globicephala) can be found — an albino short-finned pilot whale was a special attraction during fieldwork in 2017. The whale trainers of Taiji are all young men and women in their early-20s, engaging in the activity with much enthusiasm. Indeed, the whale museum and sea park are also well frequented. In the author’s three visits to Taiji, the visitors’ benches were always full. The interviews with the whale trainers, the profession of whom can hardly be understood from a Western perspective, revealed that it is inherent (national) pride that drives them. Since they contribute to the entertainment and thereby to the increased well-being of the Japanese people, they take immense pride in being able to do their job.

Whale show at the Taiji Whale Museum © Nikolas Sellheim, 2018

Whale show at the Taiji Whale Museum © Nikolas Sellheim, 2018

The perspective of well-being, therefore, does not rest on the animals, but rather on the ‘greater good’ of the Japanese people. A similar, more utilitarian approach can also be found in the different pet (or even petting) stores all over Japan, where visitors are able to pet small dogs that live their lives in cages for this very purpose. Also, Japan’s overall environmental and conservation policies are driven by utilitarian discourses (Kagawa-Fox, 2012).

The approach towards Taiji’s whaling from a purely Western perspective therefore neglects important normative elements of Japanese culture. This underlines the need for a socio-economic presentation of the hunt in non-Japanese media beyond narratives of cruelty and lack of need.

Summary and conclusion

Whaling still constitutes an activity that can be found in several places all over the world. Even though Iceland, Japan and Norway conduct commercial whaling, this cannot be compared to the uncontrolled commercial whaling of the past that decimated the numbers of the great whales dramatically. Instead, in all commercially whaling countries, the activity is strictly regulated — at least from an ecological perspective. From an animal welfare perspective, Iceland has tightened its rules after a hiatus of two months that the Minister imposed over welfare concerns. The hiatus and the subsequent resumption of whaling made waves in the international media. On the one hand, the end of Icelandic whaling was hoped for, but then, it was resumed nevertheless. For all media sources under scrutiny here, this was a major step backwards, especially from the perspective of animal welfare organisations.

The case of Taiji is somewhat different. While having gained significant media attention in the past, it is now still present, but not to a comparable degree as Iceland’s whaling. With the series published in Asahi Shimbun on the role of whaling for the community, it becomes ever more important to present these findings to a larger international audience in order for it to find some recognition as a type of hunting for food. Moreover, the socio-cultural aspects and in particular the overall utilitarian approach to animals, which constitutes a significantly different ethical narrative, should not be swept under the rug. For without taking these aspects into account, from the outside, Taiji whaling will never be comprehensible.

References – Other: